Fostering girls’ education: Afghanistan can learn a lot from Indonesia

Since the return of the Taliban to power, concern has been growing over the “Islamisation” of Afghan society – including the education sector.

Since the return of the Taliban to power, concern has been growing over the “Islamisation” of Afghan society – including the education sector.

Many fear that either schools will be shut down or girls will be excluded. This could reverse 20 years of progress in narrowing the gender gap in school enrolment.

There have been reports, for instance, about Taliban plans to enforce gender segregation, restrict women’s activities outside their homes, impose hijab norms, and replace schools with traditional madrasas (Islamic education institutions).

However, around the world, millions of girls have been schooled under similar conditions, often inspired by strict interpretations of Shariah law.

A case in point is Indonesia, where the government along with non-state religious organisations run the world’s largest network of madrasas. They have made important social contributions to educational development in remote and underdeveloped communities.

Despite the many challenges, therefore, Indonesia can serve as an important model for the Taliban of how Muslim nations and faith-based organisations can play a big role in expanding girls’ education.

Read more: As the Taliban returns, 20 years of progress for women looks set to disappear overnight

Islamic law and girls’ schooling are not in conflict

Just like Afghanistan, Indonesia has allowed madrasas to co-exist side by side with secular schools.

However, Indonesian madrasas have responded to societal needs by offering girls’ education long before other Muslim countries like Afghanistan, where most madrasas are still either single-sex, or boys only.

Indonesia’s Ministry of Religious Affairs, hand in hand with the country’s two leading Muslim organisations – the reformist Sunni organisation Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), and the education and social charity Muhammadiyah – have created a nationwide network of madrasa-educated women. Setting aside ideological differences, both have historically welcomed female students to madrasas.

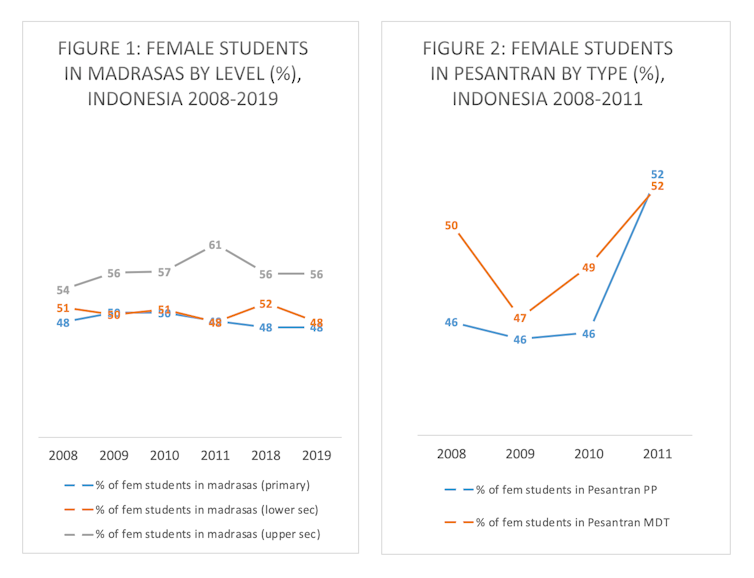

Although there has been debate over their quality, Indonesian madrasas have achieved gender parity in school enrolment. There are also more girls than boys at the upper secondary level. Even enrolment in informal or traditional Islamic boarding schools (“pesantrens”) is gender-balanced.

For Afghanistan, following in Indonesia’s footsteps can play a role in plugging the country’s supply gap of schools, particularly in remote regions.

Many parts of Afghanistan remain isolated. Poor digital infrastructure and the lack of state schools mean community-based madrasas remain the only viable option to expand girls’ schooling.

Even after the trillions of dollars invested during the US administration, around two-thirds of secondary school-aged girls in Afghanistan have been left out of school. In other words, even in the absence of Taliban rule, progress in bringing girls to school has been less than satisfactory.

Indonesia’s model can be a low-cost solution for state authorities to create educational opportunities for girls.

Another Muslim country, Bangladesh, for instance, has followed the Indonesian model of partnership with madrasas. Today, girls outnumber boys in secondary education in Bangladesh.

What’s more, even before the Taliban’s recent demands on veiling and purdah (female segregation), the Indonesian government had similarly imposed restrictive dress codes on school girls back in 2014.

So an important lesson for Afghanistan from Indonesia – as the world’s largest Muslim-majority country – is that even a preference for Shariah law is not in conflict with the global agenda to educate girls in school.

Educate to fight another day

Partnership with madrasas does in some ways undermine the full transformative power of education. However, Muslim communities should be left alone to negotiate civic rights with their ruling elites.

Bringing girls to school is the main priority right now – educated women are the best force for future social change.

In Indonesia, a number of women and parents recently spoke out against an earlier government decision to impose hijab norms. These isolated acts of protest are a byproduct of past investments that Indonesia has made in mass schooling since the 1970s. This has resulted in increasing citizen activism, voice, and a sense of empowerment among Indonesian girls and women.

This shows that, over time, a larger and critical mass of educated women can mobilise on common interests and use their literacy to negotiate better rights with state authorities.

Continuous acts of small protests in Indonesia, for instance, eventually led to a landmark decision earlier this year when the Indonesian government banned schools across the country from forcing girls to wear the hijab.

The diversity in the way that Indonesia has expanded educational opportunities for girls – despite intense conservative religious campaigns at the grassroots level – once again reminds us Islamic traditions alone are no barrier to women’s development.

Therefore, in Afghanistan, a country devastated by war and at an early stage of economic development, the world community should demand that the Taliban bring all girls to school.

In fact, the debate should not be about gender segregation and whether or not to mix religion with schooling. Education should be a priority, regardless of the form and type.

Afghanistan today has many more vocal female leaders than before, thanks to their appointment to various leadership positions in the past 20 years. The Taliban acknowledges this change, which is reflected in the regime’s recognition of the importance of girls’ schooling including access to higher education.

If past trends are sustained, schooling will empower Afghan women and help them mobilise further to negotiate more inclusive schooling in the future.![]()

M Niaz Asadullah, Professor of Development Economics, University of Malaya

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Post a Comment